Many years ago Midwestern cities grew before manufacturing of automobiles and similar heavy industrial output. Here is an excerpt from Cities of the Heartland: The Rise and Fall of the Industrial Midwest by Jon C. Teaford:

At the same time Milwaukee residents were profiting from the tanning of animal hides. The tanning business thrived in Milwaukee not only because of plentiful hides from nearby packing houses but also because of the city's proximity to the chief sources of hemlock bark in Wisconsin and Michigan. The eastern states had already exhausted this supply of this bark which was a vital ingredient to the tanning process. Consequently, tanneries gravitated westward, and by 1886 Milwaukee boasted of fifteen tanning establishments employing one thousand people.

As you can see the migration of industries often follows the path of least resistance. So tanneries migrated west to follow the supply of hemlock bark. Today there are still tanneries in Wisconsin, but

Increasing competition from abroad, however, led to the industry's

decline in the U.S. and by the end of the 1930s, only the strongest

firms remained in production. Milwaukee remains prominent in leather

production but tanning plays only a minor role overall in local

economies.

The economies of cities and regions continues to change, as they always have. The challenge is for cities like Milwaukee and Chicago to adapt to new times and embrace the change. Clinging to old times and old economies is a recipe for disaster.

Friday, September 30, 2011

Thursday, September 29, 2011

Comparative Advantage

I am a great skeptic of cities using tax incentives or other gimmicks to try and lure businesses from another region to relocate. If a company will relocate for your tax break, then it will relocate elsewhere for an even bigger tax break.

Instead I think that what drove the growth of cities in the Midwest was the comparative advantage that they held. Their location gave access to the raw materials for manufacturing. As that advantage declined manufacturing declined.

Cities in the Midwest need to focus on exploiting those advantages that give them an advantage over other cities that will allow business to germinate locally, rather than simply relocate. One advantage in the Midwest is abundant water resources.

Tied for first place are Great Lakes cities of Chicago, Cleveland and Milwaukee. Following in rank for solid water supply longevity are Detroit at number four and New Orleans at number five.

This is good news and something that these cities should advertise. They need to focus on their strengths, or as Steve Jobs said "Just get rid of the crappy stuff and focus on the good stuff". Focusing on the strengths of the region, whether that is agriculture or water or transportation or education, and stop concentrating on things that aren't working, like manufacturing.

Instead I think that what drove the growth of cities in the Midwest was the comparative advantage that they held. Their location gave access to the raw materials for manufacturing. As that advantage declined manufacturing declined.

Cities in the Midwest need to focus on exploiting those advantages that give them an advantage over other cities that will allow business to germinate locally, rather than simply relocate. One advantage in the Midwest is abundant water resources.

Tied for first place are Great Lakes cities of Chicago, Cleveland and Milwaukee. Following in rank for solid water supply longevity are Detroit at number four and New Orleans at number five.

This is good news and something that these cities should advertise. They need to focus on their strengths, or as Steve Jobs said "Just get rid of the crappy stuff and focus on the good stuff". Focusing on the strengths of the region, whether that is agriculture or water or transportation or education, and stop concentrating on things that aren't working, like manufacturing.

Wednesday, September 28, 2011

Appropriate Architecture

An example of brutalist architecture in the Loop, the Metropolitan Correctional Center

and here it is on the map

and here it is on the map

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

Tourism or: If You Build it They Will Come

Tourism can be an important source of revenue for many municipalities. Some cities, like San Francisco, have made it a staple industry. Other cities, notably those in the Rust Belt, have tried and failed to tap into the tourism market. Let’s examine some of the successes and failures.

Autoworld

Autoworld was built in the city of Flint to try and revive the economic conditions of the city during a painful period of de-industrialization. Pared with a convention center it was hoped by city leaders that tourism would revitalize the city. Both Autoworld and the convention center closed as miserable failures.

Downtown Cleveland

As the Urbanophile has so wonderfully examined for us, Cleveland’s more comprehensive approach was less a miserable failure but still ineffective at reviving the city or easing the economic woes. Building a museum and waterfront is nice but ultimately one geared towards tourism is an expensive bandaid that does little to ameliorate the salient problems facing the city.

Chicago's Waterfront

Chicago’s Millennium Park and Navy Pier are recent renovations to the city’s pre-existing museum campus downtown. Combined with Shedd aquarium, Adler Planetarium, and the Field Museums the city’s downtown has enough attractions of note that Chicago is sometimes considered a tourist destination. But let us consider this a bit further and ask why Chicago’s endeavors were more successful than some neighboring cities.

When Mayor Daley the second decided to build Millennium Park the plan was to build a park for the residents of Chicago. Without specifically catering to tourists, Daley worked with local magnates to procure private donates to offset much of the costs.

Likewise Navy Pier was not originally constructed as a tourist destination at all. Rather it was created to facilitate commercial interests and the needs of city residents and only later re-purposed as a place of retailers that cater to a tourist crowd.

In fact many of the most successful tourist attractions in Chicago were not built with the intention of gathering tourists. Instead they were built either for commercial purpose or to cater to city residents. Perhaps there is a lesson here. Midwestern cities should not use municipal funds to try and build tourist attractions. Rather, they should focus on building civic institutions that meet the needs of residents and commercial interests. If these are successful or successfully repurposed they can eventually become a place of interest that attracts tourists.

Autoworld

Autoworld was built in the city of Flint to try and revive the economic conditions of the city during a painful period of de-industrialization. Pared with a convention center it was hoped by city leaders that tourism would revitalize the city. Both Autoworld and the convention center closed as miserable failures.

Downtown Cleveland

As the Urbanophile has so wonderfully examined for us, Cleveland’s more comprehensive approach was less a miserable failure but still ineffective at reviving the city or easing the economic woes. Building a museum and waterfront is nice but ultimately one geared towards tourism is an expensive bandaid that does little to ameliorate the salient problems facing the city.

Chicago's Waterfront

Chicago’s Millennium Park and Navy Pier are recent renovations to the city’s pre-existing museum campus downtown. Combined with Shedd aquarium, Adler Planetarium, and the Field Museums the city’s downtown has enough attractions of note that Chicago is sometimes considered a tourist destination. But let us consider this a bit further and ask why Chicago’s endeavors were more successful than some neighboring cities.

When Mayor Daley the second decided to build Millennium Park the plan was to build a park for the residents of Chicago. Without specifically catering to tourists, Daley worked with local magnates to procure private donates to offset much of the costs.

Likewise Navy Pier was not originally constructed as a tourist destination at all. Rather it was created to facilitate commercial interests and the needs of city residents and only later re-purposed as a place of retailers that cater to a tourist crowd.

In fact many of the most successful tourist attractions in Chicago were not built with the intention of gathering tourists. Instead they were built either for commercial purpose or to cater to city residents. Perhaps there is a lesson here. Midwestern cities should not use municipal funds to try and build tourist attractions. Rather, they should focus on building civic institutions that meet the needs of residents and commercial interests. If these are successful or successfully repurposed they can eventually become a place of interest that attracts tourists.

Monday, September 26, 2011

More Loop redevelopment

The Loop continues to change, and I am always amazed at the transitions. For a location with the tallest building in America and a dense population of downtown workers, there is an awful lot of empty space. Today I’ll guide you through an interesting undeveloped parcel downtown in the Loop.

The Willis Tower is marked with the red A. Ignore the green arrow, it is not centered on LaSalle and Congress.

We will begin our tour on the corner of LaSalle and Congress. Here the blue line subway stop and the LaSalle St. Metra station are right next to each other and the brown/pink/purple/orange line L has stops nearby on Quincy and on Van Buren. You can see the proximity to the Willis Tower (neé Sears) north from this intersection as well.

A block from the Congress and LaSalle intersection there is an empty lot. It is adjacent to the Chicago River. At first glance it appears to be a park because people walk their dogs here. However it is for sale, and it is about 6 acres.

This is on the corner of Harrison and Wells.

As you can it is about 4 blocks to the Willis Tower and even closer to the Chicago Stock Exchange, Chicago Board of Trade, and the Chicago branch of the Federal Reserve.

The view looking northwest. The Willis tower is barely visible in the upper right hand corner.

Heading south towards Roosevelt there is an abandoned surface parking lot.

We are between Polk and Roosevelt, north of the Target, on Wells St.

Looking southeast

To the left is the grade seperated embankment for the Metra

Looking east

Looking northeast

I find it fascinating that there are undeveloped parcels so close to the intense development of downtown and the locus of transit in this area. Especially considering the parking restrictions in Downtown, having an empty parking lot is curious.

Additional reading: I'm trying to locate the site of the old Grand Central Station and see if it is still abandoned. It appears to be adjacent to the first lot we explored on Harrison and Wells and may very well be a parking lot, though I don't recall a lot on the opposite corner. Or that field may well be the former home of Grand Central. If you have any insight please let me know.

The Willis Tower is marked with the red A. Ignore the green arrow, it is not centered on LaSalle and Congress.

We will begin our tour on the corner of LaSalle and Congress. Here the blue line subway stop and the LaSalle St. Metra station are right next to each other and the brown/pink/purple/orange line L has stops nearby on Quincy and on Van Buren. You can see the proximity to the Willis Tower (neé Sears) north from this intersection as well.

A block from the Congress and LaSalle intersection there is an empty lot. It is adjacent to the Chicago River. At first glance it appears to be a park because people walk their dogs here. However it is for sale, and it is about 6 acres.

This is on the corner of Harrison and Wells.

As you can it is about 4 blocks to the Willis Tower and even closer to the Chicago Stock Exchange, Chicago Board of Trade, and the Chicago branch of the Federal Reserve.

The view looking northwest. The Willis tower is barely visible in the upper right hand corner.

Heading south towards Roosevelt there is an abandoned surface parking lot.

We are between Polk and Roosevelt, north of the Target, on Wells St.

Looking southeast

To the left is the grade seperated embankment for the Metra

Looking east

Looking northeast

I find it fascinating that there are undeveloped parcels so close to the intense development of downtown and the locus of transit in this area. Especially considering the parking restrictions in Downtown, having an empty parking lot is curious.

Additional reading: I'm trying to locate the site of the old Grand Central Station and see if it is still abandoned. It appears to be adjacent to the first lot we explored on Harrison and Wells and may very well be a parking lot, though I don't recall a lot on the opposite corner. Or that field may well be the former home of Grand Central. If you have any insight please let me know.

Friday, September 23, 2011

Chicago's waterfront then and now

Here is a delightful image of downtown Chicago from the 1960s.

This is from Chuckman's collection.

Hopefully you noticed the train yard in the lower left hand side. It is gone, replaced with Millennium Park, which you can see in the modern photo in the upper part.

Here is a similar view today

This is from the opposite side of Grant Park looking north. Can you believe I can't find a modern equivalent of the 1960s camera angle? If you find one please send it my way.

And here is the downtown skyline, this time from 1929 and again you can see the rail yards lurking in the corner.

More views of the old train yard.

Is that discoloration on the nearby buildings soot from pollution, age of the photo, or something else?

This is from Chuckman's collection.

Hopefully you noticed the train yard in the lower left hand side. It is gone, replaced with Millennium Park, which you can see in the modern photo in the upper part.

Here is a similar view today

This is from the opposite side of Grant Park looking north. Can you believe I can't find a modern equivalent of the 1960s camera angle? If you find one please send it my way.

And here is the downtown skyline, this time from 1929 and again you can see the rail yards lurking in the corner.

More views of the old train yard.

Is that discoloration on the nearby buildings soot from pollution, age of the photo, or something else?

Thursday, September 22, 2011

Chicago and Detroit: comparing interurban rail

Recently metropolitan Detroit proposed a plan to create an interurban rail system in the region. The two proposed lines would essentially restore routes that closed in the mid-80s. This plan is interesting from a comparative as well as a historic perspective. While Detroit sometimes makes an interesting comparison to Chicago, the unique history of the city can also shed some light on why things may be different between the two cities.

Comparing Detroit to Chicago is in some ways an apt comparison. The city of Detroit was, at the beginning of the 20th century, a rapidly growing city. Between 1900 and 1910 the city nearly doubled in size. Chicago had experienced similarly meteoric growth, expanding by 54% that decade, and having doubled in size in the decade prior. Both cities had a large industrial economy. And both cities had an interurban rail system, bringing commuters in from the suburbs into the city core. Finally, the two cities are less than 300 miles apart.

In Chicago the interurban lines fell on hard times and the metropolitan region created the Metra to consolidate and continue to provide passenger rail service. The first consolidation was in 1974 with the creation of the Regional Transit Authority. Today the Metra is the second busiest commuter rail system in America.

In Detroit the interurban lines fell on hard times as well. The commuter rail line from Pontiac to Detroit was administered by the Grand Trunk Railroad from 1931 until 1974 when SEMTA took it over. However by 1984 the last two commuter rail lines in metro Detroit ceased operation (Ann Arbor to Detroit in 1984 and Pontiac to Detroit in 1983).

Map of Detroit's streetcar and interurban lines from 1904

As you can see the seeds of a regional rail network similar to Chicago's Metra were spread early on, but ultimately failed to germinate. It is interesting that commuter rail service from the freight carriers folded by 1974 in both cities and administration turned to local governments. As we have seen previously good governance is important. It is also interesting that now, with the city population smaller than it was in the 1930s and less densely populated, an attempt is being made to revitalize the interurban rail network.

Chicago, for its part, has perhaps been more successful at maintaining the rail lines because of a more dense downtown. Downtown Chicago has a worker population density of 160,000 people per square mile. With downtown composed of just over 3 square miles, that gives it a worker population of almost 550,000.

Detroit, on the other hand, has a downtown worker density of 55,000 and a total worker population less than 80,000 downtown. That is less than half the density, meaning issues like traffic congestion and parking spaces aren't as large a concern. Since commuting times and parking are two important variables for deciding transit methods what may be most surprising is not that Detroit abandoned interurban rails, but that it is trying to rebuild them.

I hope to continue to explore the issue of transit in Chicago and compare it across the country in future posts, but I want to caution readers not to misconstrue my comparison between Chicago and Detroit. I wish Detroit the best of luck concerning its interurban endeavors, but I am skeptical that, due to the density of downtown Detroit, this will be successful.

Comparing Detroit to Chicago is in some ways an apt comparison. The city of Detroit was, at the beginning of the 20th century, a rapidly growing city. Between 1900 and 1910 the city nearly doubled in size. Chicago had experienced similarly meteoric growth, expanding by 54% that decade, and having doubled in size in the decade prior. Both cities had a large industrial economy. And both cities had an interurban rail system, bringing commuters in from the suburbs into the city core. Finally, the two cities are less than 300 miles apart.

In Chicago the interurban lines fell on hard times and the metropolitan region created the Metra to consolidate and continue to provide passenger rail service. The first consolidation was in 1974 with the creation of the Regional Transit Authority. Today the Metra is the second busiest commuter rail system in America.

In Detroit the interurban lines fell on hard times as well. The commuter rail line from Pontiac to Detroit was administered by the Grand Trunk Railroad from 1931 until 1974 when SEMTA took it over. However by 1984 the last two commuter rail lines in metro Detroit ceased operation (Ann Arbor to Detroit in 1984 and Pontiac to Detroit in 1983).

Map of Detroit's streetcar and interurban lines from 1904

As you can see the seeds of a regional rail network similar to Chicago's Metra were spread early on, but ultimately failed to germinate. It is interesting that commuter rail service from the freight carriers folded by 1974 in both cities and administration turned to local governments. As we have seen previously good governance is important. It is also interesting that now, with the city population smaller than it was in the 1930s and less densely populated, an attempt is being made to revitalize the interurban rail network.

Chicago, for its part, has perhaps been more successful at maintaining the rail lines because of a more dense downtown. Downtown Chicago has a worker population density of 160,000 people per square mile. With downtown composed of just over 3 square miles, that gives it a worker population of almost 550,000.

Detroit, on the other hand, has a downtown worker density of 55,000 and a total worker population less than 80,000 downtown. That is less than half the density, meaning issues like traffic congestion and parking spaces aren't as large a concern. Since commuting times and parking are two important variables for deciding transit methods what may be most surprising is not that Detroit abandoned interurban rails, but that it is trying to rebuild them.

I hope to continue to explore the issue of transit in Chicago and compare it across the country in future posts, but I want to caution readers not to misconstrue my comparison between Chicago and Detroit. I wish Detroit the best of luck concerning its interurban endeavors, but I am skeptical that, due to the density of downtown Detroit, this will be successful.

Wednesday, September 21, 2011

A walkable survey in Oak Park: Lake and Euclid

The village of Oak Park, on Chicago’s western border, makes

an interesting case study in zoning, transit, and density variables regarding

walkable urbanism. The population is

roughly 50,000 people and is 5 square miles, yielding a population density of

10,000 people per square mile. This

makes it more densely populated than Los Angeles (7,500 people per square mile) or Atlanta (4,000 people per square mile), and only slightly

less than Chicago (12,000 people per square mile). The average walkable score is 72, though as we will see the score for some areas is even higher.

Oak Park has a variety of transit options, most of which are

geared towards commuting to downtown Chicago.

There are two CTA lines of the L – the green and the blue lines – which

run through Oak Park to downtown Chicago.

There is also a Metra line with a stop in Oak Park and again a terminus

in downtown Chicago. Finally, the

Eisenhower Expressway runs through Oak Park towards downtown. All three of these transit options allow

commuters to travel from Oak Park to downtown Chicago. The green line has 3 stops in Oak Park: Lake and Harlem, Lake and Oak Park, and Lake

and Ridgeland. The blue line has 2 stops

in Oak Park: Oak Park Avenue and

Austin. The Metra stop is on Lake and

Harlem. There are two on/off ramps to

the Eisenhower Expressway: Harlem and

Austin, which are the east and west borders of the village.

The CTA also operates bus lines that run through Oak Park, and there is a Pace bus line that runs through Oak Park. Neither of the bus lines run directly from Oak Park to downtown Chicago.

The CTA also operates bus lines that run through Oak Park, and there is a Pace bus line that runs through Oak Park. Neither of the bus lines run directly from Oak Park to downtown Chicago.

The borders are drawn in black and run along Austin Blvd on the east (borders Chicago), North Ave on the north, Harlem Ave on the west, and Roosevelt Rd on the south. The green and blue lines are shaded purple and the Metra is shaded green. The Metra and the green line share the same tracks through Oak Park.

Oak Park is therefore intrinsically walkable with a robust

population density and a many excellent transit options. This offers an opportunity to carefully

survey the look and feel of density, transit incentives, and zoning

issues. We can also compare the walk score of this neighborhood to a careful survey of the intersection. This inaugural survey will focus on the intersection of Lake Street and Euclid Avenue.

This intersection provides a fascinating case study as 4

different examples of zoning and design are represented on each of the 4

corners of this intersection. First is a

single use residential building consisting of condominiums. As you can see it is built with no surface

parking allotments; residents are provided underground parking. The building is positioned right up against

the street with only a few feet between the building wall and the sidewalk. The

condominium is 4 stories.

The northeast corner of Lake and Euclid

Second is another single use building, also residential, consisting of apartments. Again there is no surface parking; residents again make use of underground parking. The apartment building is also 4 stories. Neither of these buildings are very tall. The architecture of this building should be noted for the Frank Lloyd Wright influences; Frank Lloyd Wright’s home and studio along with many early examples of his prairie style are found in Oak Park. Thus rather than being cliché the style fits the ethos of Oak Park.

Second is another single use building, also residential, consisting of apartments. Again there is no surface parking; residents again make use of underground parking. The apartment building is also 4 stories. Neither of these buildings are very tall. The architecture of this building should be noted for the Frank Lloyd Wright influences; Frank Lloyd Wright’s home and studio along with many early examples of his prairie style are found in Oak Park. Thus rather than being cliché the style fits the ethos of Oak Park.

Facing Euclid, camera pointed north

The southwest part of the building facing Euclid

The third corner is interesting in that it is mixed use; the only mixed use building on this intersection. The ground floor is composed of retail space and the remaining 3 floors are - I believe - residential space. Again this is a 4 story building, and again it has no surface parking. It does not, however, have underground parking. The ground floor businesses are a Starbucks coffee shop, a Jimmy John’s sandwich shop, a Great Clips hair salon, and Frame Up picture frame store. I believe the final store front space is vacant and for lease.

The alley behind the retail space with limited employee parking and loading zone space

A caveat: mixed use is a rather vague term but for the purposes of this blog mixed use will refer to parcel which allocate retail space mixed with non-retail space. The non-retail space does not necessarily mean residential. For example, a building might have retail floorspace on the ground level with a corporate office on the upper floors. And indeed the Art Deco building to the west has a pharmacy on the ground floor and was the former home of the Tribune’s Oak Park Leaves publication offices on the upper floors.

The final corner of Lake and Euclid has a hot dog

restaurant. One of hundreds of hot dog

places in Chicagoland, this particular hot dog restaurant is a single use

single story building and has surface parking and a drive through window. The dogs are ok but I prefer Portillos.

Proceeding north from this intersection is a block of single

family residences. These single family

residences, which are typical of Oak Park, deserve a full account of their

own. Proceeding south from this

intersection is another single use building, this time a series of 3 story

townhomes. Again there is no surface

parking, this time having the parking garage embedded in the first floor of the

building. There is also a fire

department building south of Lake and Euclid across the street from the

townhomes. Euclid is cut short by the

embankment which carries the green line train, the Metra, and a freight rail line. The green line has a stop a block away on Oak

Park Avenue.

The alley again, this time facing the townhomes

The south side of the townhomes facing the train tracks

Ground level garage parking

There are a few instructive elements in this compact space. First is the attainment of density without great building height. Simply removing surface parking has allowed 3 and 4 story buildings to produce dense neighborhoods. Second, that these dense areas can cohabitate with the automobile. By putting parking underneath the building on the ground floor or in the basement the residents can still own a car and enjoy all the benefits of having a car in the transit calculus. Indeed such a parking arrangement provides two ancillary benefits; security from petty larceny and protection from winter cold starts, the most wearing element to a car's longevity. Third, that mixed use can do more to make a small neighborhood walkable than density alone. By having that one building mixed use it created more retail storefronts (4 with 1 more possible) than the single use retail space on the opposite corner, having just one store. This does more to make this intersection walkable than if it were one single use retail plot and three 10 story apartment buildings. Finally, it demonstrates the limits of dense, mixed use neighborhoods. This intersection's retail space might not be useful to a resident that doesn't like eating hotdogs or sandwiches or want haircuts and picture frames. What you are walking to is a salient concern. Luckily for residents this neighborhood has many options; the possibility of walking further down Lake Street where retail spaces continue on, taking the green line train to a shopping destination, driving, or taking a bus. However, as we have seen before sometimes the incentives point towards driving.

Overall the walk score for this intersection is an outstanding 95. I hope that you found this microstudy to be an interesting

case study for some of the issues involving urban living, especially density,

walkability, and cars.

Labels:

apartments,

cars,

Condominiums,

density,

mixed use,

oak park,

parking,

transit,

Walkable

Tuesday, September 20, 2011

The wrecking ball

This picture by David Schalliol is fascinating for many reasons.

This home is on Chicago's South Side. It is in walking distance to the green line elevated at 35th, the Metra station at 35, and the red line station on 35th. It is close to some parks and White Sox baseball field. It is also near the Dan Ryan Expressway. It is about 4 miles to Chicago's tallest landmark, downtown's Willis Tower (neé Sears Tower).

As you can see it is an astonishingly beautiful home. This sort of architecture is getting rare.

This house is slated for demolition. It is fascinating how a single family residence close to downtown and accessible to transit can face the wrecking ball. It is easy to lament the destruction of such a magnificent home, but sometimes the alternative is more terrible. The alternative is feral houses. If I were a resident of this neighborhood I would much rather see an empty field than an empty house.

This highlights the importance of good governance. The city of Chicago established the Fast Track Abatement program in 1993 to facilitate the removal of blight. The city of Detroit established the Land Bank in 2008 for the same purpose. During that 15 year lag the city of Detroit lost considerable population. Feral houses are a symptom of a larger dysfunction in Detroit; a reflection of the failure of the political institutions of the city. If Detroit established a similar program in the mid 90s much of the excess housing supply would be cleared, preventing the build up of blight.

This home is on Chicago's South Side. It is in walking distance to the green line elevated at 35th, the Metra station at 35, and the red line station on 35th. It is close to some parks and White Sox baseball field. It is also near the Dan Ryan Expressway. It is about 4 miles to Chicago's tallest landmark, downtown's Willis Tower (neé Sears Tower).

As you can see it is an astonishingly beautiful home. This sort of architecture is getting rare.

This house is slated for demolition. It is fascinating how a single family residence close to downtown and accessible to transit can face the wrecking ball. It is easy to lament the destruction of such a magnificent home, but sometimes the alternative is more terrible. The alternative is feral houses. If I were a resident of this neighborhood I would much rather see an empty field than an empty house.

This highlights the importance of good governance. The city of Chicago established the Fast Track Abatement program in 1993 to facilitate the removal of blight. The city of Detroit established the Land Bank in 2008 for the same purpose. During that 15 year lag the city of Detroit lost considerable population. Feral houses are a symptom of a larger dysfunction in Detroit; a reflection of the failure of the political institutions of the city. If Detroit established a similar program in the mid 90s much of the excess housing supply would be cleared, preventing the build up of blight.

Labels:

blight,

bronzeville,

Chicago,

demolition,

Detroit,

south side

Monday, September 19, 2011

A look back at Chicago's growth

To get some appreciation of the growth of the Northeast United States in the early 20th century I recommend reading this brief online book The Greatest Highway in the World. It is a survey of the cities that lie along the New York central line: New York to Chicago and everything in between.

90 years ago Chicago's rise to prominence could be summarized as follows:

"It is the financial centre of the west and the metropolis of the richest agricultural section in the country. These circumstances have contributed to make it the greatest grain and live stock market in the world. But its accessibility to the raw materials of industrial development has also made it a great manufacturing city. Chicago has more than 10,000 factories and the output of its manufacturing zone is probably more than $3,000,000,000 annually. The principal industries and manufactures are meat packing, foundry and machine shop products, clothing, cars and railway construction, agricultural implements, furniture, and (formerly) malt liquors."

Chicago has been described as being like a snake; periodically it sheds its skin and reinvents itself. In the 1920s it was a manufacturing power. Even the agricultural fruits of the Plains were put through the industrial operations of the meat packing plants. By the 1970s many of the components of Chicago's manufacturing age had dissipated and the city slowly reinvented itself. It is still in that process of reinventing itself.

A closer examination of these contributions to Chicago's past development shows the structural changes of the region that forced the city to shed its past. Specifically the commodities that were used as inputs to Chicago's industries have changed. For starters the agricultural output of the Great Plains has diminished relative to the country overall.

By 2006, the regional distribution of production had shifted substantially. The Central region’s share of U.S. production value decreased to 30.8%, while the Northeast region’s share fell from 9.6% in 1949 to 5.7% in 2006. The big increase was in the Pacific region, whose share roughly doubled over the 57-year period, from 8.3% of U.S. agricultural output value in 1949 to 16.3% of the 2006 total. As shown in Table 1, the output quantity index grew faster in the Pacific, Northern Plains, and Mountain regions than the nation as a whole.

So too has the manufacturing components of the region changed. The iron ore, a crucial component of 20th century manufacturing, was primarily mined from the nearby Lake Superior region. However the output of this region has declined since the publication of the Greatest Highway in the World.

During the twentieth century, high grade ore, originally so plentiful on all three iron ranges, became less available and less profitable to mine. The cost of underground mining became more prohibitive, and the owners of Michigan's mines began to search for other methods of tapping the iron riches of Lake Superior. Many of the mining operations, such as the Lake Superior Iron Company, were absorbed by larger corporations. Between World War I and World War 11, the total tonnage of iron ore shipped fluctuated drastically: in 1920, Michigan shipped over eighteen million tons of ore. In 1921, 1931, 1932, 1933, and 1934 Michigan shipped less than half that amount.

Since 1920 the Midwest declined in agriculture and iron production. And since 1920 Chicago has declined in manufacturing these raw materials into finished goods. These changes can be seen in the face of the city itself, in good and bad ways. From re-purposing manufacturing sites into condos to blight and empty fields, the face of the city has changed.

Of course this isn't unique to Chicago. At the opposite end of the Greatest Highway in the World, New York City also saw manufacturing decline.

As John Gunther wrote in his 1947 best-seller, Inside U.S.A., New York City was "incomparably the greatest manufacturing town on earth." In 1947 over thirty-seven thousand city establishments engaged in manufacturing, employing nearly three-quarters of a million production and 200,000 non-production workers.

Today there are 233,000 manufacturing jobs in more than 10,000 New York City industrial businesses. Quite a decline from the almost 1 million of 1947.

New York had been a major manufacturing center since the earliest days of the republic. In 1950, 28 percent of the city's employed workers were in manufacturing, two points above the national figure. The percentage of the city workforce employed in manufacturing had been declining since 1910, when it had peaked at just over 40 percent. However, except during the 1930s, the actual number of manufacturing workers in the city had risen each decade of the century. When World War II ended, New York manufacturing was at an all-time high.

In 1947, New York had more manufacturing jobs than Philadelphia, Detroit, Los Angeles, and Boston put together.

It isn't surprising then that Chicago is, in some ways, following New York's path in how it reinvents itself.

90 years ago Chicago's rise to prominence could be summarized as follows:

"It is the financial centre of the west and the metropolis of the richest agricultural section in the country. These circumstances have contributed to make it the greatest grain and live stock market in the world. But its accessibility to the raw materials of industrial development has also made it a great manufacturing city. Chicago has more than 10,000 factories and the output of its manufacturing zone is probably more than $3,000,000,000 annually. The principal industries and manufactures are meat packing, foundry and machine shop products, clothing, cars and railway construction, agricultural implements, furniture, and (formerly) malt liquors."

Chicago has been described as being like a snake; periodically it sheds its skin and reinvents itself. In the 1920s it was a manufacturing power. Even the agricultural fruits of the Plains were put through the industrial operations of the meat packing plants. By the 1970s many of the components of Chicago's manufacturing age had dissipated and the city slowly reinvented itself. It is still in that process of reinventing itself.

A closer examination of these contributions to Chicago's past development shows the structural changes of the region that forced the city to shed its past. Specifically the commodities that were used as inputs to Chicago's industries have changed. For starters the agricultural output of the Great Plains has diminished relative to the country overall.

By 2006, the regional distribution of production had shifted substantially. The Central region’s share of U.S. production value decreased to 30.8%, while the Northeast region’s share fell from 9.6% in 1949 to 5.7% in 2006. The big increase was in the Pacific region, whose share roughly doubled over the 57-year period, from 8.3% of U.S. agricultural output value in 1949 to 16.3% of the 2006 total. As shown in Table 1, the output quantity index grew faster in the Pacific, Northern Plains, and Mountain regions than the nation as a whole.

So too has the manufacturing components of the region changed. The iron ore, a crucial component of 20th century manufacturing, was primarily mined from the nearby Lake Superior region. However the output of this region has declined since the publication of the Greatest Highway in the World.

During the twentieth century, high grade ore, originally so plentiful on all three iron ranges, became less available and less profitable to mine. The cost of underground mining became more prohibitive, and the owners of Michigan's mines began to search for other methods of tapping the iron riches of Lake Superior. Many of the mining operations, such as the Lake Superior Iron Company, were absorbed by larger corporations. Between World War I and World War 11, the total tonnage of iron ore shipped fluctuated drastically: in 1920, Michigan shipped over eighteen million tons of ore. In 1921, 1931, 1932, 1933, and 1934 Michigan shipped less than half that amount.

Since 1920 the Midwest declined in agriculture and iron production. And since 1920 Chicago has declined in manufacturing these raw materials into finished goods. These changes can be seen in the face of the city itself, in good and bad ways. From re-purposing manufacturing sites into condos to blight and empty fields, the face of the city has changed.

Of course this isn't unique to Chicago. At the opposite end of the Greatest Highway in the World, New York City also saw manufacturing decline.

As John Gunther wrote in his 1947 best-seller, Inside U.S.A., New York City was "incomparably the greatest manufacturing town on earth." In 1947 over thirty-seven thousand city establishments engaged in manufacturing, employing nearly three-quarters of a million production and 200,000 non-production workers.

Today there are 233,000 manufacturing jobs in more than 10,000 New York City industrial businesses. Quite a decline from the almost 1 million of 1947.

New York had been a major manufacturing center since the earliest days of the republic. In 1950, 28 percent of the city's employed workers were in manufacturing, two points above the national figure. The percentage of the city workforce employed in manufacturing had been declining since 1910, when it had peaked at just over 40 percent. However, except during the 1930s, the actual number of manufacturing workers in the city had risen each decade of the century. When World War II ended, New York manufacturing was at an all-time high.

In 1947, New York had more manufacturing jobs than Philadelphia, Detroit, Los Angeles, and Boston put together.

It isn't surprising then that Chicago is, in some ways, following New York's path in how it reinvents itself.

Friday, September 16, 2011

A Chicago survey from the 1930s

Here is a short youtube video from the 30s giving a brief overview of Chicago.

There are a few things to note. First the high car traffic on Michigan Ave at the 1:00 mark. Second, the wide streets and boulevards mentioned around the 2:30 mark. Third is the stockyards at the 4:30 mark, which no longer exist.

There are a few things to note. First the high car traffic on Michigan Ave at the 1:00 mark. Second, the wide streets and boulevards mentioned around the 2:30 mark. Third is the stockyards at the 4:30 mark, which no longer exist.

Thursday, September 15, 2011

Without cars

One item of contention I often read amongst the urbanist crowd is the issue of cars. Many people that enjoy city life and urbanism in general look at the automobile as a source of the decline of the American city, either directly or indirectly. While I can certainly see the issue cars present, especially in regards to parking, I find the issue to be rather complex.

Urban decline in America is approximately correlated with the permeation of the automobile in American culture. However it is also approximately correlated with the decline in manufacturing. It is also approximately correlated with desegregation. Since correlation is not necessarily causation I am reticent to place blame on one factor or even a host of factors.

Still the goal of reducing the scope of cars in city life is an interesting proposition. My own experiences have shown me that going carless in the 3rd largest city in America is rather difficult. But first, some background statistics.

Chicago is America's third largest city with a population around 2.7 million. It is the 4th most densely populated major city in America. It has America's second largest rapid transit system by number of stops and number of track miles. It is the third largest by ridership. However, it is 7th largest by rider density, or 6th if you consider the New York systems as one. New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Washington DC, and surprisingly Los Angeles all have a higher ridership per mile ratio.

The green lines represent the Metra's lines, and the purple lines represent the CTA's lines

Upon closer examination, the CTA's rapid transit lines look like a more condensed version of the Metra commuter rail system. The lines draw in from the edge of the city and converge downtown. So even if you are within walking distance of a CTA line, it most likely will only take you downtown. For many Chicagoans the most useful function of the L is to commute downtown for work.

Getting around the city without a car means using one of three modes of transportation: the train, a bus or cab, and walking. This can be very time consuming. It can also be expensive.

Here is a good example: If you want to go from a residence near the Clinton green line stop to a restaurant near the Ashland green line stop it is a 1.3 mile 25 minute walk but a mere 4 minute train ride. However that ride will cost you $2.25 each way, which is more expensive than driving - assuming that parking is free. Then again if you invest in a monthly unlimited pass then, depending on how often you use your card, this trip might be cheaper than driving.

I hope that this helps illustrate that there are many factors that influence the mode of transportation in Chicago. Travel time is a consideration, and car congestion is certainly a factor in Chicago. Price of traveling is another issue. Therefore the decision to walk, take a train, drive, take a bus, or take a cab is determined by a diverse criteria. Each element affects the other.

Going carless in Chicago can be rather difficult and isn't something I would attempt unless I lived downtown where the walkability is high and distance between train stations low.

Urban decline in America is approximately correlated with the permeation of the automobile in American culture. However it is also approximately correlated with the decline in manufacturing. It is also approximately correlated with desegregation. Since correlation is not necessarily causation I am reticent to place blame on one factor or even a host of factors.

Still the goal of reducing the scope of cars in city life is an interesting proposition. My own experiences have shown me that going carless in the 3rd largest city in America is rather difficult. But first, some background statistics.

Chicago is America's third largest city with a population around 2.7 million. It is the 4th most densely populated major city in America. It has America's second largest rapid transit system by number of stops and number of track miles. It is the third largest by ridership. However, it is 7th largest by rider density, or 6th if you consider the New York systems as one. New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Washington DC, and surprisingly Los Angeles all have a higher ridership per mile ratio.

The green lines represent the Metra's lines, and the purple lines represent the CTA's lines

Upon closer examination, the CTA's rapid transit lines look like a more condensed version of the Metra commuter rail system. The lines draw in from the edge of the city and converge downtown. So even if you are within walking distance of a CTA line, it most likely will only take you downtown. For many Chicagoans the most useful function of the L is to commute downtown for work.

Getting around the city without a car means using one of three modes of transportation: the train, a bus or cab, and walking. This can be very time consuming. It can also be expensive.

Here is a good example: If you want to go from a residence near the Clinton green line stop to a restaurant near the Ashland green line stop it is a 1.3 mile 25 minute walk but a mere 4 minute train ride. However that ride will cost you $2.25 each way, which is more expensive than driving - assuming that parking is free. Then again if you invest in a monthly unlimited pass then, depending on how often you use your card, this trip might be cheaper than driving.

I hope that this helps illustrate that there are many factors that influence the mode of transportation in Chicago. Travel time is a consideration, and car congestion is certainly a factor in Chicago. Price of traveling is another issue. Therefore the decision to walk, take a train, drive, take a bus, or take a cab is determined by a diverse criteria. Each element affects the other.

Going carless in Chicago can be rather difficult and isn't something I would attempt unless I lived downtown where the walkability is high and distance between train stations low.

Wednesday, September 14, 2011

The South Loop: A slow transition

Chicago's South Loop is fascinating in the diversity of elements present. Here, around the corner from the Roosevelt station, is a derelict building condemned by the city and slated for demolition.

The building to the immediate left is a historic building. To the immediate right is an empty lot. You can tell by examining the building on the far right that there once was a building where the empty lot sits.

The Roosevelt station is both a red line subway station as well as a green/orange line elevated station. It is just a few blocks from Printer's Row and Grant Park. Easy access to the main portion of downtown marked with the large A on the map.

On Michigan Avenue there is a vacant lot for sale. Grant park is directly across the street. As you can see it is in walking distance from the Roosevelt station.

The parcel was scheduled for auction on July 27th, 2010 and the suggested starting bid was 9 million dollars. It was previously priced around 33 million.

As a note of reference the dividing line between north and south in Chicago is Madison Avenue. This area is no further south from Madison Ave as the upscale Streeterville is north from Madison.

I am obligated to observe too the way that the South Loop has developed. The former mayor Richard Daley moved from his traditional neighborhood in Bridgeport to the South Loop. So I don't want to give the impression that this is a down and out neighborhood. It is a neighborhood that is slowly transforming into an upscale residential neighborhood. If you look closely at the above picture you will see the balconies of the condos that are near this parcel.

The building to the immediate left is a historic building. To the immediate right is an empty lot. You can tell by examining the building on the far right that there once was a building where the empty lot sits.

The Roosevelt station is both a red line subway station as well as a green/orange line elevated station. It is just a few blocks from Printer's Row and Grant Park. Easy access to the main portion of downtown marked with the large A on the map.

On Michigan Avenue there is a vacant lot for sale. Grant park is directly across the street. As you can see it is in walking distance from the Roosevelt station.

The parcel was scheduled for auction on July 27th, 2010 and the suggested starting bid was 9 million dollars. It was previously priced around 33 million.

As a note of reference the dividing line between north and south in Chicago is Madison Avenue. This area is no further south from Madison Ave as the upscale Streeterville is north from Madison.

I am obligated to observe too the way that the South Loop has developed. The former mayor Richard Daley moved from his traditional neighborhood in Bridgeport to the South Loop. So I don't want to give the impression that this is a down and out neighborhood. It is a neighborhood that is slowly transforming into an upscale residential neighborhood. If you look closely at the above picture you will see the balconies of the condos that are near this parcel.

Tuesday, September 13, 2011

Printer's Row: Chicago's first condominiums

Chicago's first condominiums were established in Printer's Row. Here what was once factory and warehouse space for the printing industry was converted into residential space in the 1970s. This was in some ways a watershed moment for Chicago.

On the map you can see the centrality of this location. It is near the lake and Grant Park and in the locus of the main rapid transit lines in Chicago.

As you can see from the map, it is in walking distance to the blue line subway at LaSalle, the red line subway at Harrison, the brown/orange/purple line elevated at Van Buren, and the Metra at LaSalle.

Its walkable score is a perfect 100.

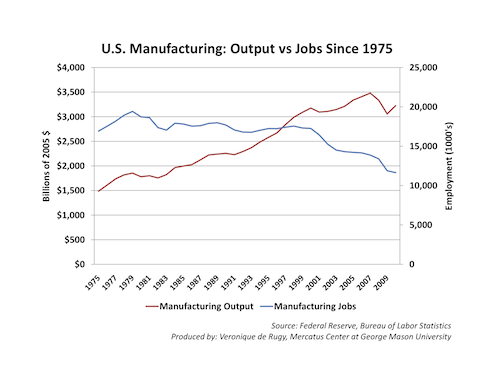

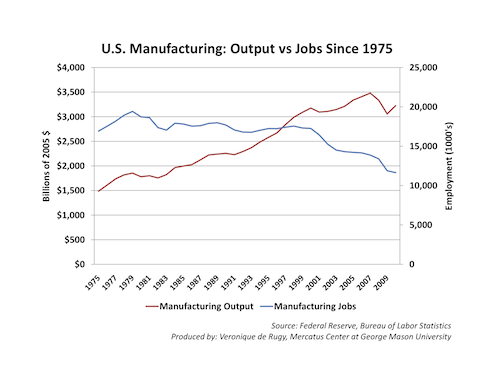

One can survey this neighborhood in many ways, but one way to think of it is the transitional nature of industrial cities in America. Over the last 40 years the number of people working in manufacturing has declined, despite the overall increase in manufacturing output.

Manufacturing jobs peaked in the late 70s and have steadily declined both in terms of percent of the total workforce and total number of workers.

The re-purposing of Printer's Row from manufacturing to residential use coincides with the overall decline in manufacturing employment in America.

On the map you can see the centrality of this location. It is near the lake and Grant Park and in the locus of the main rapid transit lines in Chicago.

As you can see from the map, it is in walking distance to the blue line subway at LaSalle, the red line subway at Harrison, the brown/orange/purple line elevated at Van Buren, and the Metra at LaSalle.

Its walkable score is a perfect 100.

One can survey this neighborhood in many ways, but one way to think of it is the transitional nature of industrial cities in America. Over the last 40 years the number of people working in manufacturing has declined, despite the overall increase in manufacturing output.

Manufacturing jobs peaked in the late 70s and have steadily declined both in terms of percent of the total workforce and total number of workers.

The re-purposing of Printer's Row from manufacturing to residential use coincides with the overall decline in manufacturing employment in America.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)